|

Publishing

Information

Social Showman

Survey Graphic

November 1936

Vol 25, No. 11, p. 618.

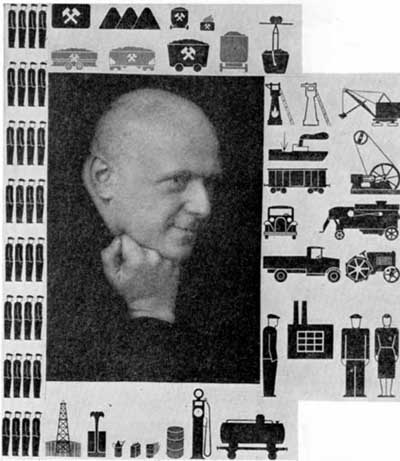

THE Big Man who created the Little Man is with us from overseas

this fall. Though the two of them have not been heralded on Broadway,

the Little Man is a sound actor—and Otto Neurath is his impresario. The

significant Little Man, who represents a hundred thousand or maybe a

million of us, made his first appearance in America in the pages of

Survey Graphic in 1932. Row on row like the chorus of a review,

or among the symbols of the things men buy and sell and eat and use, or

perhaps at a halting place in man's long pilgrimage from savagery to

peace and plenty, he has become the hero of act after act in which he

may not even enter the stage at all. In business roles he signifies the

man earning over $7500, or owning an automobile, or belonging to country

clubs; or—in the field of social welfare—having a job, the toothache,

tuberculosis, naturalization papers, or no job, or what not. But he is

not really so elementary as all that. The Little Man was begot in a bed

of statistics, trained by economists, and styled by imaginative

designers. The true secret of his significance, and of the significance

of all Neurath's methods, is that Neurath, the social showman, is also a

philosopher. Authenticity in research, and precision in visualizing the

finding of the experts, do not cramp the style of Neurath s large mind

- Like the man in the moon, whom he resembles when his great

countenance is reflective, Neurath s orbit swings clear round the earth.

He sets the imagination on fire as Van Loon, or H. G. Wells, sometimes

does simply by giving us a surprising glimpse of ourselves in a moving

social procession. But with this difference. Neurath is never carried

away by his fancies, or his day dreams, into conjecture. He is, first of

all, a mathematician, disciplined in the natural sciences.

- In bringing about the "renascence of hieroglyphics" Neurath

wrested from the hierarchy of his own scientific colleagues their

monopoly of learning. Our civilization, he feels, is still under the

sway of a Middle Ages pattern in which a word language is the property

of one class alone. In the Middle Ages, it was the monks with their

Latin. Today it is the scientists whose polysyllabic books are over the

heads of most of us. Yet if democratic cooperation toward the solution

of complex problems is not to fail, we must all understand the great

forces which affect our lives.

- To Neurath the pie-chart, the bar-chart, the fluctuating lines

of the graph-makers and the map makers are almost as inadequate as fancy

words. Neurath is never without a huge pencil rooted to his hand to

chart the ideas that transcend words. Not that he is inarticulate. A

sociologist and the son of a sociologist, a logician and the husband of

a logician, he knows and speaks the language of the scientists. In

conversation, especially in German, his vocabulary carries all the

nuances of ideas and images. In his English, which he has sharpened into

the colloquial by leading dozens of detective stories on his voyages to

America, he is precise, exact. But no matter how fluently one may

describe something, he feels that to be fully understood, it must be

visualized. Back of the automobile and the skyscraper, for example, lies

r.p.m.s. and complex mathematical formulas, translated into action by

the engineers. Back of Neurath's pictures and museum exhibits lie

profound research, statistics transformed into ideas, ideas then

designed into a picture narrative, a drama of social interpretation.

- NEURATH is a practical man. For years he has worked with

research and educational organizations in half a dozen countries besides

the United States. He created and directed the famous Gesellschafts und

Wirtschaftsmuseum of his native city of Vienna. It was in that museum

that he blossomed out as a showman, the Barnum of man's life and work.

- That was in 1924. Neurath was then, at forty-two, a mature

social scientist of growing repute; his household was a center of

practical as well as intellectual discussion. Wartime experience in the

economic division in charge of civilian supplies in Poland had thrown

him into first hand contact with the source and flow of commodities. His

teaching experience. in Heidelberg and Vienna, had developed his gift

for relating science to daily life. Then as general secretary of the

Austrian Federation for Housing and Garden Cities, he expressed himself

through posters and graphs and popular expositions that indicated his

bent. When Vienna began its great program of rehabilitation and social

welfare, Neurath started the Social and Economic Museum. There, with a

group of first rate collaborators in graphic work, he directed the

transformation of facts and figures into easily understood, dramatic

exhibits—which, by virtue of their relation to each other, told their

story almost without words, as no museum displays ever had done before.

- Traditionally, a museum director is a collector of exhibits, the

keeper of a mausoleum, where scattered relics fag the brain and tire the

feet. Boldly Neurath ventured into the Museum of the Future. His museum

was located on the first floor of the city hall. It was a dynamic

representation of the social, economic and cultural synthesis of the

city. At night, when the rooms were open for workmen, he introduced

novel illumination effects and movies.

- "It was called a museum," Neurath says. "It was really a

permanent exposition. It was not enough to show what the city did with

its taxes, what opportunities and responsibilities Vienna offered to its

citizens, and vice versa. Our exhibits and apparatus also made

comparisons with other cities and countries and other periods of

history."

- By popular demand, tiny branches were added in another quarter

of the city. These were the sideshows. In the main museum, in the heart

of the city, housing, health, education, science were dramatized, not as

lone exhibits, competing with all else, but through charts, apparatus,

naturalistic photographs and schematic models, as part of a living

society. The social effects of inventions (for instance, typewriters

giving women a new occupation and a new economic standing) or welfare

activities (clinics nipping disease in the bud) were shown as part of

the whole pageant of life. Always, man himself was the exhibit, man the

Viennese in a great and interrelated world.

- Neurath's skill in appealing to the general public was proved by

the length of time individual visitors remained without tiring. In

ordinary museums the strain of digesting hundreds of unrelated exhibits

is almost as great as the strain of listening to a half dozen different

languages all at once. To attractiveness and informativeness Neurath

added unity—a pattern. which utilized his great background of history,

biology, economics and political science, the whole stated for you not

in words but in things and pictures. "I tried to make it as dramatic as

New York's Broadway at night," Neurath has said. "Broadway is the most

exciting exhibit in the world. In the electric signs all the texts are

in English, all the letters are in Latin type; their size, direction,

motion and colors are standardized into half a dozen simple patterns.

Social facts can be shown in an analogous system of standardized

simplicity that he who runs may understand."

- To be sure, Neurath respects and draws upon advertising and

propaganda experience. But the product he has to sell is enlightenment.

Hence his charts, as was his museum, are not composed of competing

parts, or messages, but aim toward visual cooperation. Only once has

Neurath gone outside the ordinary channels of expression to compete with

advertisements. He and his staff having worked up a poster about a

housing exposition, he wanted it printed so that it would receive the

maximum attention in competitive display. He finally hit upon a

distinctive green color, not to be matched on any billboard in Vienna He

made that color the exposition's own.

- In 1934 the Austrian government wiped out Neurath's museum in

Vienna. But he succeeded in rescuing a large part of its exhibits, and

they were sent to Holland and added to the permanent exposition of the

International Foundation for Visual Education, of which he is the

director. That organization, founded the year before as a result of

worldwide interest in the Vienna method, still functions. Neurath lives

at its international headquarters at The Hague.

- There, with several members of his original staff, he has built

up, as it were, a whole "pictorial esperanto" for visual education. His

pictorial language symbols have become as universal as notes in music,

though much easier to understand. Dutch educators in the East Indies,

for example, are interested in the possibility of using them in

classrooms to give their pupils a new sense of connection with the world

far away—something not in any books that Malaysians will ever read. At

The Hague he and his institute have completed two books with

ISOTYPE pictures, edited by C. K. Ogden, author of The

Meaning of Meaning. Their titles, "Basic by Isotype" and

"International Picture Language" give new currency to the device here

pictured. ISOTYPE not only means what its Greek roots

signify, "always the same symbols," but is a coy acrostic using the

initials International System of Typographical Pictorial Education. The

Little Man is his trademark, his professional signature.

- Neurath is sufficiently intuitive to work by remote control, and

turns out a constant stream of ideas and exhibits for such organizations

as the National Tuberculosis Association, which urged his present visit

to the United States under the auspices of the Oberlander Trust. Each

special assignment becomes his pet. One devoted to social insurance once

packed to capacity for a week a small room in Dresden, when much more

spacious exhibits by others went almost neglected. But as a generous

teacher he does not think in terms of competing with the work of others.

Indeed, he has welcomed and encouraged others to utilize his own

technique.

- Only in initiated circles in the United States, Sweden Holland,

England, the USSR and half a dozen other countries, is he a celebrity.

He, the complete showman, is a world figure, a name that the little men

themselves scarcely know.

- In harness, he is like the elephant that is his whimsical

personal signature (as characteristic as Whistler's butterfly!) patient,

persistent, a tower of strength and a respecter of tradition, a man who

can work with others, yet who contributes something uniquely his own.

Neurath's great body and broad brow and surprising adaptability suggest

a good-humored socially-minded pachyderm. Yet it is notable that a man

of his dynamic and brilliant originality has recruited and worked with a

permanent, well-trained and harmonious staff. Although not an artist he

has inspired and formulated the most extraordinary designs ever used to

give life to statistics, geography, natural resources and social forces.

All because he knows that "a simple picture remembered is better than

accurate figures forgotten," by young and old, by people of all levels

of intelligence, by scholars and illiterates. Likewise a dynamic

exposition. Even a lantern-slide lecture or movie, which he uses when no

other medium seems portable enough, can not be seen or felt except

during the course of a performance. A picture chart can be turned to, an

exposition can be visited, time and time again. They have a permanent

theatrical effect; they are continuous social shows. A show's a show,

anywhere, and Neurath is a showman—his theater the world, and all of us

the actors. Few men of our time have laid their hands so close to the

dramatic plot, elusive as a gypsy trail, that marks our destiny on this

planet.

|